Heritage

Picture: ©English Heritage - NMR Aerofilms Collection.

The aerial photograph above was taken on the 25th May 1937 and shows the plant in production but apparently near to bankruptcy. The plant continued for a few more years before closing in 1945. The buildings were derelict by the 1960's, demolition and nature have removed most of the traces but the occasional block of concrete can still be seen as a reminder to the history of the site.

Originally Nelson's was a lime works and evidence of the extensive lime workings remains today. The lime was later used as the raw material to make cement.

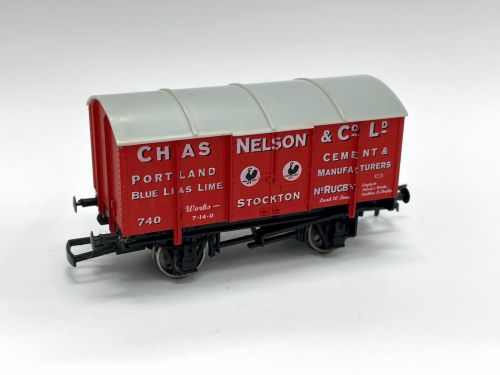

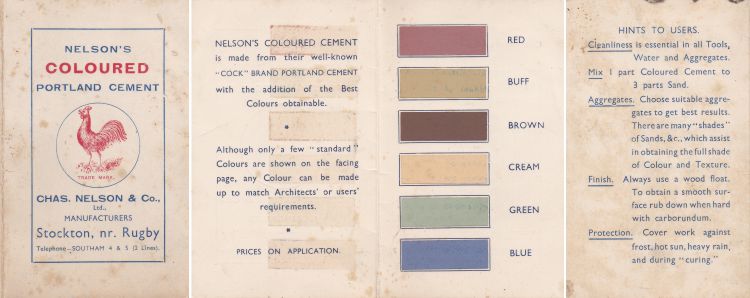

Dates vary but it is generally accepted that cement began production in 1857 but true Portland cement was not made until later around 1872. Boats would bring in coal and take out the famous "Cock" brand cement. The railways came along in 1895 as the L&NWR, Weedon-Leamington branch but both modes of transport can be seen working side by side and advertisements of the time offered transport by road, rail or canal.

Dates vary but it is generally accepted that cement began production in 1857 but true Portland cement was not made until later around 1872. Boats would bring in coal and take out the famous "Cock" brand cement. The railways came along in 1895 as the L&NWR, Weedon-Leamington branch but both modes of transport can be seen working side by side and advertisements of the time offered transport by road, rail or canal.

History of the works:

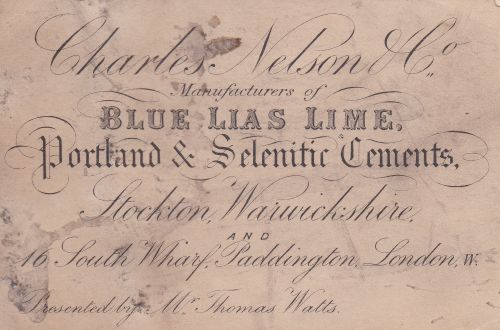

The Charles Nelson Cement Company was located at Stockton, near Southam, some ten miles south-west of Rugby and the same distance west of Daventry.

There were small limestone quarries in the area from earlier dates and by about 1766 lime kilns were said to be ‘springing up’ in nearby Long Itchington. The Blue Lias limestone in Warwickshire trends from South West to North East through the Rugby to Southam area. The rock was laid down some 200 million years ago as alternating layers of Clay and Limestone. ‘It seems likely that the Blue Lias clay layers represent periods of thousands of years, when swollen rivers that resulted from a wetter climate flushed billions of tons of mud into the Jurassic sea. The limestone beds might indicate drier periods, resulting in a clearer, sunlit sea.

When the common land was enclosed in Stockton in 1792, the church was awarded a plot of land in ‘Long Highlands’. The plot contained ‘a rock of limestone’, and was sold to John Tomes and Charles Handley of Warwick for £885, they were the chairman and chief engineer respectively of the Canal Company.

When the common land was enclosed in Stockton in 1792, the church was awarded a plot of land in ‘Long Highlands’. The plot contained ‘a rock of limestone’, and was sold to John Tomes and Charles Handley of Warwick for £885, they were the chairman and chief engineer respectively of the Canal Company.

The Warwick and Napton canal (a branch of the Oxford canal) was started in 1795. Charles Handley was appointed engineer at 350 guineas a year. In August 1795, he suggested varying the line of the Canal from Warwick to join at Napton-on-the-Hill, with a saving of £50,000, and usefully passing near his limestone quarry! He was given 300 guineas for his extra work, and the renamed Warwick & Napton Canal was formally opened on 19 December 1799, and opened for trade on 19 March 1800.

The lime, and later the cement, industries developed, because of the improved access to the Warwickshire coalfields that allowed transport of Coal into, and Lime out of, the Stockton area. In the nineteenth century, there were at least eight lime works and many more kilns were in operation at various dates, typically located adjacent to the canal. In 1874 it was said of Stockton that ‘The Blue Lias limestone abounds in this Parish and is considered to be the best in England.

The Nelson cement and lime works history is closely associated with that of George Nelson, Dale & Co of Warwick, gelatine and isinglass manufacturers whose business is still flourishing and is now part of the Davis Gelatine Group. Lime is used in the manufacture of gelatine.

George Nelson of Warwick was a timber merchant and earlier a chemist and during the 1830s he began the manufacture of gelatine and other meat extracts. In 1844 he started producing his own lime for use in that process, although he was not listed in Stockton until 1860.

After George Nelson's death in 1850, the two works [gelatine and lime] were supervised by relatives until 1856, when his eldest son, Charles, was 22 years old and took control. The manufacture of cement was introduced at the lime works which traded separately as Charles Nelson & Co. Charles’s younger brothers later assumed control of the gelatine business.

In 1870, Charles Nelson took his brothers, George and Montague, into partnership together with Thomas Blyth and William Blackstone, who were London lime and cement merchants, although the Deed of Partnership itself did not mention the two Nelson brothers!

In 1877, Charles Nelson died of Bright's Disease, aged only 43, leaving a widow and ten children.

In 1880, George Henry Nelson, Edward Montague Nelson, Thomas Philip Blyth and William Widger Blackstone formed a Partnership to carry on the business. They would later convert it to a company with shares.

The Nelson family was also developing shipping and property in Australia and New Zealand and establishing a meat refrigeration business.

In April 1886, the firm became a company with a share capital of £100,000. The main shareholders were Thomas Philip Blyth of Southam; William Widger Blackstone of St Pancras, both lime and cement merchants; George Henry Nelson of Warwick, manufacturer; and Edward Montagu Nelson, of Ealing, manufacturer.

After the death in 1890, of Blackstone, aged only 47, a Special Resolution was passed, ‘That the salary of Mr Thomas Philip Blyth, the sole Managing Director of the Company, be increased from the sum of £500 per annum … to £800 …’. He also died five years later, aged 64, in 1896, after a long and painful illness. In October 1896, his sons, George Blackstone Blyth and Charles Edward Blyth were appointed Joint Managing Directors at salaries of £500 per annum; these increased to £800 in 1904 (when Montague Nelson and Howard Blyth were also directors), and £1000 in 1907.

Trade was depressed. In December 1904, Lister-Kaye wrote: ‘The building trade all over the Midlands is very bad. Nelsons & Rugby are very slack, the latter particularly so & having filled all their stores, are working short time.’ In January 1905, he wrote, ‘Nelsons are as slack as us’. In 1906, Charles and George Blyth had to guarantee £6000 of the Nelson overdraft with Lloyds Bank.

In 1909, the auditors’ report pointed out ‘… that although the Profits have decreased in recent years, the Managerial Salaries have very much increased …’. The annual profits had steadily increased from 1886 until 1900, and had fallen thereafter, with a half year’s loss of £200 in 1909.

The company had an overdraft of some £17,000 and the bank required some reassurances; in 1910, Nelsons issued 20 Debentures of £1000 each at an interest rate of 4½% which were held by the Trustees for Lloyds Bank. The Company was required to reduce its borrowing by £1000 before the end of 1912, and then by a further £1000 by the end of each successive year. The debentures were transferred to new Trustees in 1931, both former Trustees having died.

Little is know about trade in the First War, there would have been a considerable demand for cement. However, a printed letter, showed that the War Office were controlling production.

"We beg to thank you for your order ... Owing to our works having been commandeered by the War Office, we regret that we are not allowed to execute any orders without first obtaining from them a permit. We are applying … for a permit and will write … on hearing from the War Office".

The details of Nelson’s trading in the 1920s and 1930s are also unknown, but trading was difficult. In late 1930 an overdraft of £10000 with Lloyds Bank was agreed against a Second Debenture, allowing the 1906 guarantee of £6000 from C. E. Blyth and G. B. Blyth to be relinquished.

In 1930, C. E. Blyth resigned, and George Blackstone Blyth, who had been Joint M.D. since 1896, was appointed sole M.D. for 7 years from December 1930, at £1200 pa. He was re-appointed in December 1937, for a further 7 years, at £2000 pa plus a bonus of 10% of the profits.

The neighbouring firm, Kaye & Co., went bankrupt in 1934 and was bought by Rugby Portland Cement. The Cement Makers Federation was formed, to avoid cut-throat competition, and a sales quota for each company was agreed, Nelsons being awarded 40,000 tons in 1934. Later, in 1939 Nelson had a quota of 0.7325%.

In November 1944, Nelson’s War Bonds were redeemed, possibly when Nelsons was acquired by the Rugby Portland Cement, who may have had an interest as early as 1937, as when Halford Reddish became M.D. of Rugby Cement in March 1933, and took the company public in 1935, he was also listed as Managing Director of Charles Nelson. It seems that Rugby Cement had a significant shareholding by that date. An accounts ledger ‘Stockton’ for the period 1932 to 1944, was probably started when Reddish introduced more effective accounting procedures. The story that Rugby Cement acquired Nelson’s and immediately closed it, does not stand up to examination.

In 1945, Rugby Cement announced that ‘… they had acquired a substantial proportion of the share capital of Charles Nelson …’, which allowed Rugby to use Nelson’s transport Licenses. Whilst the works were reported to have closed in 1949, Charles Nelson, as a subsidiary company was still in existence with Halford Reddish as Managing Director in 1952, and it was not until 1978 that the remaining Nelson Share Capital was bought by Rugby. The Charles Nelson Company was used to retain the various transport fleet licenses and was still as part of the Rugby Group in 1979, when it was responsible for transport, and for operating the RPC Transport Ltd.

The site was cleared of structures in 1968, the army being invited to use it for training demolition engineers!

After aquiring the land, a local man gave us the following transcript of his connections with Nelsons or locally known as Cally Cement Works:

Cally Cement Works – Charles Nelson and Son

Early 1900s view of the ladder bridge, for that is what the older locals call it. Local children learnt to swim here because the water in the canal was warm from the Cally Works processed water outflow. I remember this bridge being in a very precarious state from my childhood (I’m 61 now), when we used to walk as a family from High Street, Stockton, where we lived at that time, to the Boat Pub, the green pub as we kids called it (now mainly red), just up on the main Rugby Road, on a Sunday evening. A similar picture but with the works visible can be seen on page 5 of the Stockton section of www.windowsonwarwickshire.org.uk. This website gives a very accurate picture of the lovely life at the time in the village and some of the old characters, such as Archdeacon Colley. People weren’t materially rich but most of them rarely went hungry, as the Company houses had pig sties and large vegetable gardens. I own this old postcard but sadly I don’t know who the people are.

My family have been associated with Stockton and lime and cement working from at least the mid 1800s; first through my Granny Teresa’s mother’s family, the Mullises, as a William Mullis, probably a Great Uncle is shown as a lime worker, in the 1881 census. His niece Mary Ann married my Grandad William Worrall, who was the Rural Letter Carrier for several villages in the area.

The next connection was through my Grandad George Harry Lockley, who came to Stockton from Offchurch, to work at Cally in the early 1900s and married my Granny Teresa. During all of that time, almost up to the Second World War, a number of uncles and great uncles also worked there.

My Grandparents had twelve children, so there were always plenty of “willing” volunteers to take Grandad’s lunch up to the works, during the school lunch break. My Aunt Freda, now nearly 95, was one and she has many happy memories of those days, even though it was quite a long way from where they lived in Victoria Terrace, Napton Road in Stockton. They had to do it she said.

Freda recalls on one occasion seeing one of the horses, which were used to shunt the railway sidings, being treated by a vet, having been badly injured in a collision with a wagon.

Later, when my Dad’s youngest brother Ron, now in his eighties, took over the lunch job, he found it easier to some extent, because he had a bike. However the difficulty was getting the bike and Grandad’s dinner over the two or three stiles on the way to Cally, without spilling any of the gravy from the bowl. It was a full hot dinner after all, with a bowl covered by a “clorth”, as I remember my Granny pronouncing it.

Grannies brother, Great Uncle Ted, who is shown as a child in 1881 was working at Cally in 1901, as did two uncles; my dad Fred’s second youngest brother, Uncle Wilf Lockley, who drove the little “Lister diesel” quarry railway engines or “Dinkums” as he always referred to them; and Uncle Wilf Warner, who married my Dad’s oldest sister Tess and also worked in the quarry. He once had a lucky escape when driving an excavator from the top of the quarry and hooked the quarry side, tipping the whole machine over the edge. He just managed to jump clear.

The father of my Aunt Phyllis, who married my Dad’s oldest brother, also George, Bill “Tetty” Rawbone, was a steam locomotive driver at the works. He was reputedly sacked by the owner George Blythe, who lived at Stockton House, for blowing the whistle on his locomotive too loud and long, when the Labour Party were elected into government for the first time. Tetty later kept the Green Man Pub in the neighbouring village of Long Itchington, where Auntie Phyllis played the piano on a Saturday night for many years.

Also Granny’s older sister Lucy Worrall married a Jack Barrott, who became Manager of the Reliance Lime Works, between Stockton and Long Itchington. His brother Ike (Isaac) also worked at Cally.

I personally remember the old houses up at Cally being lived in, when I was a child but the shop which had been there had closed by this time, as was the works. Eventually the houses were demolished but the majority of the works was left standing derelict for many years. My brother and I and some of our friends used to cycle up there and explore all the old buildings, which by then were in a pretty dangerous state, with corrugated iron hanging off some of the walls and roofs. Once we found some old round advertising sheets, with long defunct cement companies on, including the famous Cock Brand, which I presume would have been attached to the cement sacks. Although we took them home, I think they have now been lost.

Later as the old railway line became a nature trail, most of the surface buildings were demolished but the old air raid shelters and the old water tower, complete with the wonderful “Nelson’s Cock Brand Cement”, still survives. I hope the new owners can at least preserve that. The picture is from 2005.

Later my Dad, his youngest brother Ron and myself and my brother Pete have all worked for the successors of Nelsons, Rugby Cement (now of course Cemex).

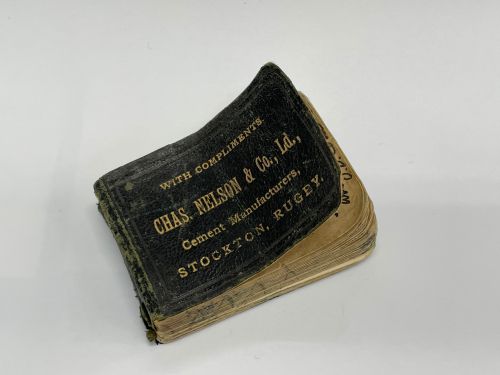

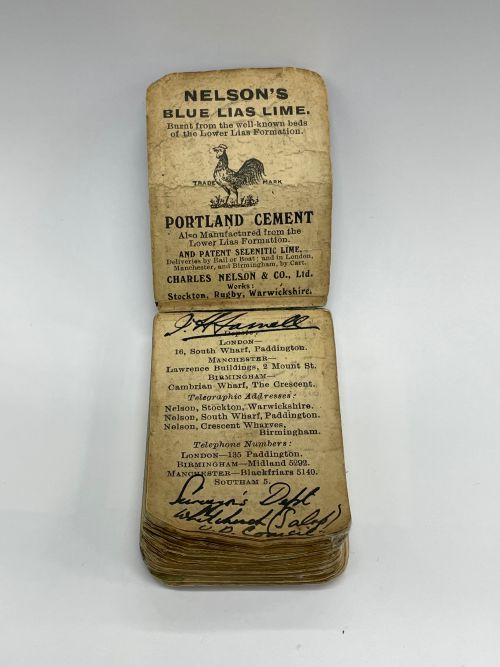

Memorabilia

Since we bought the land, many items with links to Nelson's has come to us. Some found in the ground, some bought on eBay but many just handed to us by well-meaning locals. Thank you to all of them.

Many of the items are photographs. See below.